Overlord has asked me to do some more articles for this site. Now I have my Day job to do, and these articles actually take a bit of time, so I said I would try to stick up the odd piece on a Wednesday. These will likely be shorter and a different format to the Sunday article. They will not be a regular feature either. So without any further ado, lets get on with it.

On the 14th I had special (written and signed in triplicate) permission from my other half to disappear down to Dorset. To visit the Bovington Tank Museum. This would be my first visit, and thanks to a nice chap named Ed, and a very nice lady called Roz (who was too shy to get on camera), they agreed to open up the Vehicle Conservation Centre so I could have a walk round some of their rarer pieces.

As I had my camera with me I figured you lot might like to see some of the results.

First up we have this Vickers light Amphibious tank:

You can see the usual Carden Loyd running gear. More interestingly its got a Vickers HMG in the turret. Much like early Cruiser tanks and the Matilda. So it could theoretically mount a .50 cal Vickers HMG, meaning you might in the far future see it in game.

Next we have the D3E1 Wheel-cum-track:

An idea that was all the rage in the inter-war years. The idea is you can use the wheels on road, but when you need it as a tank you raise the wheels up and off you set. So in theory the best of both worlds.

However you also get twice the complexity and it is likely to break. That said the Germans did use a wheel-cum-track design in the Second World War.

Next we have the Excelsior:

A tank that you all will know from World of Tanks.

Next a very fetching Stridsvagn L-60:

Hopefully we'll see it somewhere in either the Combined EU or a separate Swedish tech tree.

Now we come to a Saladin:

As I've long been joking: World of Armoured Cars, you all know it makes sense. What better advert for it than something this cute?

There was also this little oddity:

Now it was defiantly Canadian, so either a Ram or a Grizzly (I forget which) but it has a gun with a muzzle brake. So I guess a US 76mm.

As I pressed deeper I found a real prize:

As you can see this is the QinetiQ ACAVP. QinetiQ is what's left of the UK Governments defence research department. The tank its self was a technology test vehicle, and is made out of plastic. Yes that's right, its really made out of plastic armour.

Now those of you who are in the UK know that the week I went down to Bovington parts of the UK were doing a passable impression of a submarine. As I was clicking away I didn't know it but my camera had gotten a bit wet and the pictures weren't being recorded. This was the last picture that I could recover from my camera before it gave up the ghost completely:

So can you ID the tank?

After Bovington I got back to my hotel only to find the water from the river already washing over the road, and the hotels garden was submerged. So I quickly grabbed my gear and checked out despite me being due to stay another night. I timed it just right as I had to drive through three floods on the way home, one of which was on a motorway!

The Good news is I have a much better camera now, and I'll have to make plans to go back.

Purpose of this blog

Dmitry Yudo aka Overlord, jack of all trades

David Lister aka Listy, Freelancer and Volunteer

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Cold Gold

Convoy QP11 steamed out of Murmansk on the 28th of April 1942 and passed the Kola Inlet into the frozen Arctic seas, lashed by wind and water. The temperature could easily fall to -10 degrees, and the ships decks would often become sheets of ice.

QP11 consisted of 13 freighters and their escorts. One of the warships that accompanied the convoy was HMS Edinburgh, a Town class light cruiser (Similar to HMS Belfast in London). She was the convoy’s command ship, and located within one of her magazines was 4570 Kg of solid gold. This was a part payment from Russia to the UK and USA as part of the Lend Lease program. In 1942 this was worth 1.5 million pounds.

Two days later HMS Edinburgh had detached herself as forward picket, and gone ahead on patrol. As she reached the limit of the 20 mile circuit, she prepared to return to the convoy. Thinking they were out of the immediate danger her crew were stood down from general quarters status which they had been maintaining for the previous 48 hours while in the area of most risk.

A few hundred yards away lay the German submarine U456 which had been lying in wait for the convoy. The submarine had only two torpedoes left after its patrol, and it watched the zigzagging HMS Edinburgh. As chance would have it Edinburgh turned onto a new course just as she got within firing range of the U-boat. If she had turned the other way, this entire story wouldn't have happened.

At 1555 on the 30th of April the Edinburgh's ASDIC operator reported a contact, very near by and they were closing on it. It was judged to be a false contact.

Realising that the cruiser would maintain the course she currently had, the U-boat fired both torpedoes.

None of Edinburgh's crew saw the torpedoes as they streaked towards her. Both were perfectly aimed and slammed into her starboard side. The first torpedo struck her amidships and tore through to the boiler room and shattered Edinburgh's fuel tanks. The blast had also cracked open the deck, dropping about 50 sailors into a storage tank which then began to flood with oil.

The second torpedo hit the stern and caused the most critical damage. The explosion blew the deck plates up, wrapping the armour around the rear turrets and rendering them utterly inoperable. The blast caused a similar effect on the stern pushing the hull downwards to form a sort of keel from the damage.

Two of the four propellor shafts were also destroyed, as was the clothes stores and ships power was lost. Of the guns, only B turret could still be operated, but it could not be rotated nor did it have director control.

Spewing heavy fuel oil, and listing badly the Edinburgh drifted to a halt, utterly at the mercy of the U-boat. Luckily the U-boat lacked any further means of attack.

Signalling for assistance the Edinburgh drifted helplessly. The crew were shivering and freezing as they were exposed to the worst of the weather without the clothing to protect them. However the rest of the convoy was currently under attack, and so no help could be dispatched.

Eventually a small force of two Soviet destroyers and two British destroyers were freed from the defence of the convoy and reached the stricken Edinburgh at about 1730.

By now the damage control parties had managed to get Edinburgh's propulsion working and she could make a maximum speed of 8 knots on one shaft. Unfortunately though due to the damage caused by the second torpedo she could only steam in a giant circle.

One of the destroyers (HMS Forester) managed to attach a tow line to Edinburgh's bow. The tow line broke under the strain with such force it sounded like a gunshot, and the cable wrapped itself around a stanchion. Four further attempts all ended the same way.

As the officers devised a new plan, suddenly a lookout yelled a warning about a submarine three miles astern. HMS Forester immediately went to full power and healed over towards the contact to engage. As she approached the spot where the U-boat had crash dived her captain ordered her to slow ahead so the ADISC could get a reading.

HMS Forester’s throttles had jammed wide open, so the ship overshot. By the time she could be brought back under control the submarine was long gone. A couple of depth charges were fired in the vain hope of hitting. Again chance appeared, and unknown to the crew of the HMS Forester one of the depth charges did damage the U-boats periscope.

The new plan to tow the Edinburgh was successful. The line was attached to the stern of the ship, and one of the destroyers could counter the turn. It did mean that the top speed was two knots, and with about 200 miles to go it would take at least four days to reach Murmansk.

So again the crew stood too, with out clothing, food or sleep in the bitter Arctic night. Some relief was provided by hot cocoa, but only after a vessel big enough to boil it in was found. As it turned out this was one of the officers bath tubs.

At 0600 the next day the two Russian destroyers signalled they were almost out of fuel and had to return to Murmansk. On a more positive note a Russian tug and four Minesweepers were already on the way to support Edinburgh.

Overnight a force of German destroyers had attacked the Convoy but had been seen off, knowing the Germans were in the area in force the Admiral considered his position and issued the following signal to her escorts:

"In the event of attack by German destroyers, Foresight and Forester are to act independently taking every opportunity to defeat the enemy without taking undue risks to themselves in defending Edinburgh. Edinburgh is to proceed wherever the wind permits, probably straight into it. If the minesweepers are present they are also to be told to act independently, retiring under smoke screens as necessary."

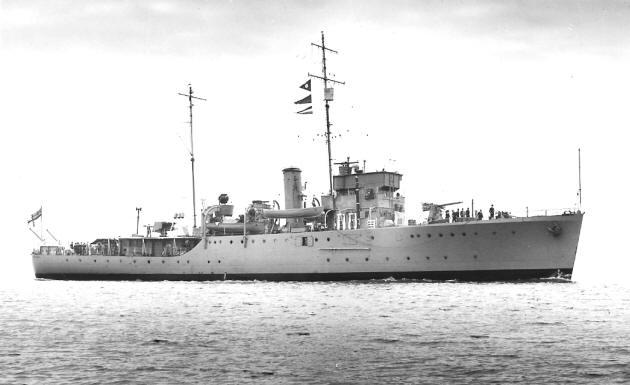

At 1800 the Rubin, the Russian tug appeared, and about midnight the four minesweepers hove into sight. It was then found that the tug had insufficient power, so one of the minesweepers had to assist in the towing. The other minesweepers split up to take positions round the damaged Edinburgh. The rear most minesweeper (HMS Hussar) suddenly spotted three German destroyers following the massive oil slick that Edinburgh was bleeding from her broken hull.

The tiny minesweeper launched an attack on the vastly superior destroyers. Armed with two 4 inch guns HMS Hussar faced off against the German ships, who were each armed with four 5.9 inch guns. Hussar was forced to retreat in short order.

HMS Hussar's brief action had served its role of rear guard. The firing of the guns had warned the rest of the flotilla. Both the destroyers increased to top speed and turned to take on the Germans. Edinburgh cast off her tow ropes, raised her battle flag and increased to her top speed of 8 Knots, turning in a huge circle. Several German salvo's fell astern of the battered cruiser.

The two Royal Navy destroyers HMS Forester and HMS Foresight turned towards the Germans and fired spreads of torpedoes. On the HMS Edinburgh one of the gunnery officers threw open a hatch on the top of B turret, which was still unable to traverse. Using nothing more than his judgement he waited until the ships bows bore on one of the German ships. Yelling the command to fire the three guns he managed to bracket the German destroyer Hermann Schoemann.

The Germans broke off laying smoke, and a swirling melee occurred. Ships of both sides were using the cover of mist and squalls or laying smoke screens as they raced around at speed taking snap shots at targets as they appeared. Suddenly the HMS Edinburgh found herself pointing at the Hermann Schoemann again, and again the 6" guns roared. The first two shells bracketed the wildly manoeuvring destroyer and the third smashed into its hull destroying its boilers. The Hermann Schoemann drifted for the remainder of the battle and was later scuttled.

Elsewhere HMS Forester turned to fire a broadside upon a German ship, only to be engaged by both enemy destroyers. The punishment HMS Forester took caused her to lose power to her engines and like the Hermann Schoemann she started to drift, as the Germans closed in. HMS Foresight came to her aid, spewing a smoke screen and she deliberately drove between the Germans and their prey. HMS Foresight took the salvo meant for HMS Forester which caused her heavy damage as well leaving her with one operational gun and damaged boilers.

To cover their withdrawal the Germans launched a spread of torpedoes at the temporarily immobilized HMS Forester. Unable to do anything but watch the ships company held their breath for the explosion. It never came as both torpedoes streaked under the hull.

Chance had one final part to play in the battle. One of the wildly fired torpedoes drew a line straight into the circling Edinburgh. It hit amidships on the port side, almost directly opposite the hole from the previous hit.

B turret was firing at the retreating Germans when the torpedo hit, the Gunnery officer was blown out of the hatch and just managed to catch himself on the edge of the turret before falling onto the deck or overboard.

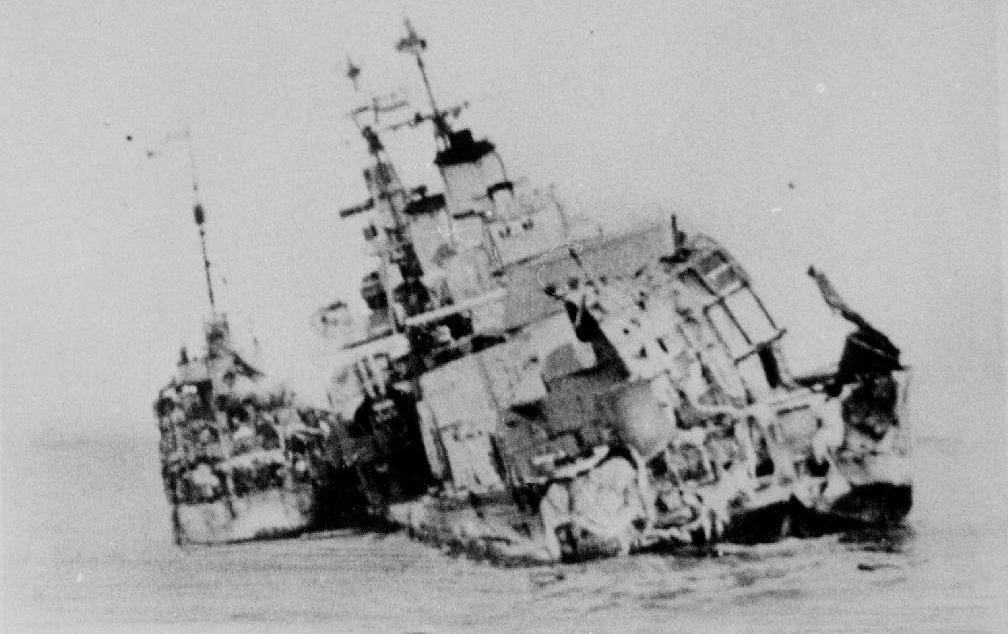

With the battle over, and only a few deck plates holding the HMS Edinburgh together the order to abandon ship was given. The minesweepers pulled alongside and took off the remaining ships company.

After everyone was off the ships pulled away from HMS Edinburgh and waited for her to sink. After fighting to stay afloat for so long the habit seemed ingrained in the battered ship, and she stubbornly refused to heel over.

One of the minesweepers then fired twenty rounds at the floating carcass. these had no effect other than starting several small fires. Two salvo's of depth charges were then dropped close to the hull in an attempt to break HMS Edinburgh's back, but still to no effect.

Finally HMS Foresight used her one remaining torpedo on HMS Edinburgh. The defiant cruiser rolled onto her side then broke in two with the stern sinking immediately. The bow reared up before slipping backwards under the water.

But what of the gold? Before you all start reaching for your wetsuits you should know that most of the 465 bars were recovered in 1980 and 1986.

But five bars are still unaccounted for! Each bar is worth in the region of $400,000.

|

|

| HMS Edinburgh |

A few hundred yards away lay the German submarine U456 which had been lying in wait for the convoy. The submarine had only two torpedoes left after its patrol, and it watched the zigzagging HMS Edinburgh. As chance would have it Edinburgh turned onto a new course just as she got within firing range of the U-boat. If she had turned the other way, this entire story wouldn't have happened.

At 1555 on the 30th of April the Edinburgh's ASDIC operator reported a contact, very near by and they were closing on it. It was judged to be a false contact.

Realising that the cruiser would maintain the course she currently had, the U-boat fired both torpedoes.

None of Edinburgh's crew saw the torpedoes as they streaked towards her. Both were perfectly aimed and slammed into her starboard side. The first torpedo struck her amidships and tore through to the boiler room and shattered Edinburgh's fuel tanks. The blast had also cracked open the deck, dropping about 50 sailors into a storage tank which then began to flood with oil.

The second torpedo hit the stern and caused the most critical damage. The explosion blew the deck plates up, wrapping the armour around the rear turrets and rendering them utterly inoperable. The blast caused a similar effect on the stern pushing the hull downwards to form a sort of keel from the damage.

Two of the four propellor shafts were also destroyed, as was the clothes stores and ships power was lost. Of the guns, only B turret could still be operated, but it could not be rotated nor did it have director control.

Spewing heavy fuel oil, and listing badly the Edinburgh drifted to a halt, utterly at the mercy of the U-boat. Luckily the U-boat lacked any further means of attack.

Signalling for assistance the Edinburgh drifted helplessly. The crew were shivering and freezing as they were exposed to the worst of the weather without the clothing to protect them. However the rest of the convoy was currently under attack, and so no help could be dispatched.

|

| Bridge of HMS Belfast, showing the weather that could be encountered |

By now the damage control parties had managed to get Edinburgh's propulsion working and she could make a maximum speed of 8 knots on one shaft. Unfortunately though due to the damage caused by the second torpedo she could only steam in a giant circle.

One of the destroyers (HMS Forester) managed to attach a tow line to Edinburgh's bow. The tow line broke under the strain with such force it sounded like a gunshot, and the cable wrapped itself around a stanchion. Four further attempts all ended the same way.

As the officers devised a new plan, suddenly a lookout yelled a warning about a submarine three miles astern. HMS Forester immediately went to full power and healed over towards the contact to engage. As she approached the spot where the U-boat had crash dived her captain ordered her to slow ahead so the ADISC could get a reading.

HMS Forester’s throttles had jammed wide open, so the ship overshot. By the time she could be brought back under control the submarine was long gone. A couple of depth charges were fired in the vain hope of hitting. Again chance appeared, and unknown to the crew of the HMS Forester one of the depth charges did damage the U-boats periscope.

The new plan to tow the Edinburgh was successful. The line was attached to the stern of the ship, and one of the destroyers could counter the turn. It did mean that the top speed was two knots, and with about 200 miles to go it would take at least four days to reach Murmansk.

So again the crew stood too, with out clothing, food or sleep in the bitter Arctic night. Some relief was provided by hot cocoa, but only after a vessel big enough to boil it in was found. As it turned out this was one of the officers bath tubs.

At 0600 the next day the two Russian destroyers signalled they were almost out of fuel and had to return to Murmansk. On a more positive note a Russian tug and four Minesweepers were already on the way to support Edinburgh.

Overnight a force of German destroyers had attacked the Convoy but had been seen off, knowing the Germans were in the area in force the Admiral considered his position and issued the following signal to her escorts:

"In the event of attack by German destroyers, Foresight and Forester are to act independently taking every opportunity to defeat the enemy without taking undue risks to themselves in defending Edinburgh. Edinburgh is to proceed wherever the wind permits, probably straight into it. If the minesweepers are present they are also to be told to act independently, retiring under smoke screens as necessary."

At 1800 the Rubin, the Russian tug appeared, and about midnight the four minesweepers hove into sight. It was then found that the tug had insufficient power, so one of the minesweepers had to assist in the towing. The other minesweepers split up to take positions round the damaged Edinburgh. The rear most minesweeper (HMS Hussar) suddenly spotted three German destroyers following the massive oil slick that Edinburgh was bleeding from her broken hull.

|

| HMS Hussar |

|

| The German force consisted of two of these Type 1936A's |

|

| ...and the Hermann Schoemann |

The two Royal Navy destroyers HMS Forester and HMS Foresight turned towards the Germans and fired spreads of torpedoes. On the HMS Edinburgh one of the gunnery officers threw open a hatch on the top of B turret, which was still unable to traverse. Using nothing more than his judgement he waited until the ships bows bore on one of the German ships. Yelling the command to fire the three guns he managed to bracket the German destroyer Hermann Schoemann.

The Germans broke off laying smoke, and a swirling melee occurred. Ships of both sides were using the cover of mist and squalls or laying smoke screens as they raced around at speed taking snap shots at targets as they appeared. Suddenly the HMS Edinburgh found herself pointing at the Hermann Schoemann again, and again the 6" guns roared. The first two shells bracketed the wildly manoeuvring destroyer and the third smashed into its hull destroying its boilers. The Hermann Schoemann drifted for the remainder of the battle and was later scuttled.

Elsewhere HMS Forester turned to fire a broadside upon a German ship, only to be engaged by both enemy destroyers. The punishment HMS Forester took caused her to lose power to her engines and like the Hermann Schoemann she started to drift, as the Germans closed in. HMS Foresight came to her aid, spewing a smoke screen and she deliberately drove between the Germans and their prey. HMS Foresight took the salvo meant for HMS Forester which caused her heavy damage as well leaving her with one operational gun and damaged boilers.

To cover their withdrawal the Germans launched a spread of torpedoes at the temporarily immobilized HMS Forester. Unable to do anything but watch the ships company held their breath for the explosion. It never came as both torpedoes streaked under the hull.

Chance had one final part to play in the battle. One of the wildly fired torpedoes drew a line straight into the circling Edinburgh. It hit amidships on the port side, almost directly opposite the hole from the previous hit.

With the battle over, and only a few deck plates holding the HMS Edinburgh together the order to abandon ship was given. The minesweepers pulled alongside and took off the remaining ships company.

After everyone was off the ships pulled away from HMS Edinburgh and waited for her to sink. After fighting to stay afloat for so long the habit seemed ingrained in the battered ship, and she stubbornly refused to heel over.

One of the minesweepers then fired twenty rounds at the floating carcass. these had no effect other than starting several small fires. Two salvo's of depth charges were then dropped close to the hull in an attempt to break HMS Edinburgh's back, but still to no effect.

Finally HMS Foresight used her one remaining torpedo on HMS Edinburgh. The defiant cruiser rolled onto her side then broke in two with the stern sinking immediately. The bow reared up before slipping backwards under the water.

But what of the gold? Before you all start reaching for your wetsuits you should know that most of the 465 bars were recovered in 1980 and 1986.

But five bars are still unaccounted for! Each bar is worth in the region of $400,000.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)